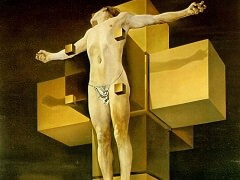

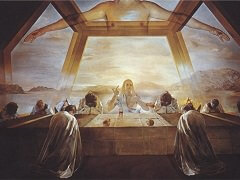

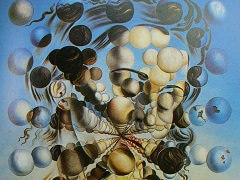

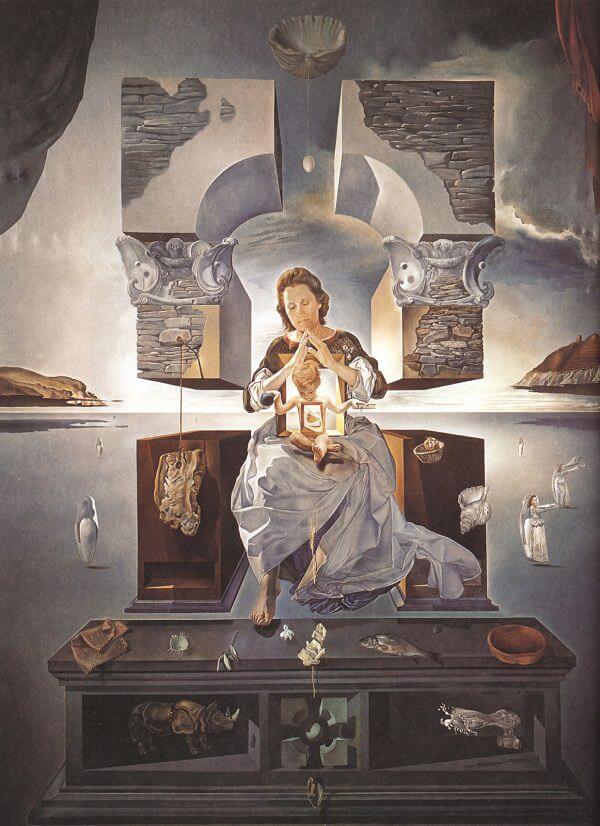

The Madonna of Port Lligat, 1950 by Salvador Dali

In 1950, Dali painted a second and final version of The Madonna of Port Lligat, an immense painting that he regarded as his greatest work to date. The work was painted on such a colossal scale that it took the artist five months to complete and, when the work was shipped to New York for its debut exhibition in November 1950, it was too large to fit on the elevator or stairs and had to be hoisted by ropes to the sixth-floor Carstairs Gallery. As the artist gleefully explained to newspaper reporters at the time, this larger version was 'completely changed' from the earlier study, with the focal point no longer on the rapturous face of the Madonna, but instead on the Christ child, in the center of whose body now appeared the bread of the Eucharist. Dali's explanation for this modification of his original conception was that:

Modern physics has revealed to us increasingly the dematerialization which exists in all nature and that is the reason why the material body of my Madonna does not exist and why in place of a torso you find a tabernacle 'filled with Heaven.' But while everything floating in space denotes spirituality it also represents our concept of the atomic system - today's counterpart of divine gravitation."

Although the basic iconography of the painting, drawn from the Italian Renaissance altarpieces featuring an enthroned Madonna by Piero della Francesca and Carlo Crivelli, remained the same as the 1949 version, the vibrant blue color scheme of the earlier work was replaced by a darker blue-gray palette, while the increased scale of the final painting required a plethora of new symbols to be added. Some of these were familiar to Dali's repertoire, such as the basket of bread that is suspended beside Gala. However, other objects represented new obsessions, like the cuttlefish bones that double as angel wings in which the figure of Gala can at times be discerned. Another important feature of the painting is the first appearance of the rhinoceros, a recurring motif in Dali's late work, which stands in the shadows of the recessed, predella-like space beneath the Madonna's foot. The shadow of the rhinoceros emphasizes its disconnected, levitating horn, a minor detail that nonetheless signals the genesis of what would become the artist's quintessential atomic emblem. Once again, Gala was depicted as the Virgin Mary, while Juan Figueres, a six-year-old boy from Cadaques, was used as the model for the infant Jesus. Both figures are suspended in midair, like particles of atomic matter, while directly above their heads a symbolic ostrich egg hangs by a thread. This is a medieval symbol of the immaculate conception, based on the myth that the female ostrich hatched its eggs by exposing them to sunlight without being impregnated by the male bird.