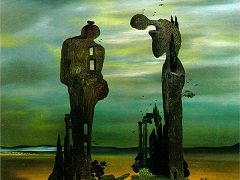

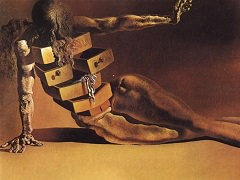

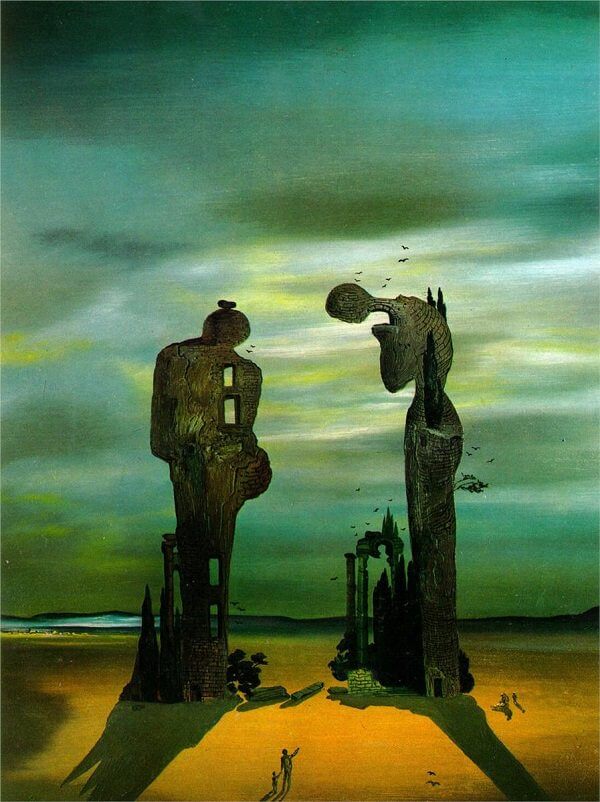

Archeological Reminiscence of Millet's 'Angelus', 1933 by Salvador Dali

Jean-François Millet is noted for his scenes of peasant farmers; he is one of the Realism art movement founders. Millet was an important source of inspiration for Vincent van Gogh, particularly during his early period. Millet's late landscapes would serve as influential points of reference to Claude Monet's paintings of the coast of Normandy.

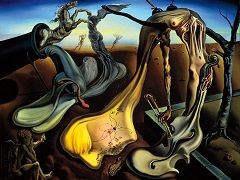

Millet's Angelus was reproduced frequently in the 19th and 20th centuries. Van Gogh drew his own version of The Angelus (after Millet). Salvador Dali was also fascinated by this work, and wrote an analysis of it, The Tragic Myth of The Angelus of Millet. But rather than seeing it as a work of spiritual peace as Impressionists do, Dali believed it held messages of repressed sexual aggression. Dali was also of the opinion that the two figures were praying over their buried child, rather than to the Angelus. Dali was so insistent on this fact that eventually an X-ray was done of the canvas, confirming his suspicions: the painting contains a painted-over geometric shape strikingly similar to a coffin.

In typical fashion, Dali personalized this theme, using it to try to pin down the hidden reasons for his long fascination with the painting The Angelus by Jean-Francois Millet. He idiosyncratically interprets Millet's figures as being posed in the attitudes of praying mantises; for Dali, the Millet painting became an unconscious parable of female sexual power. The female figure, to the right, poses expectantly, ready to pounce, while the male, head bowed in defeat, vainly tries to protect hi; genitals with his hat. Dali's own long-established fears of female sexuality, of impotence and castration, now found a portentous pictorial source, a new "paranoiac-critical" focus. As a consequence, Dali often turned to this theme as though to expunge his fears.

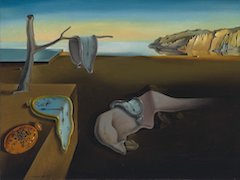

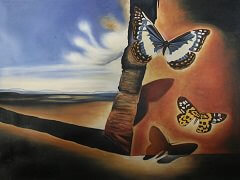

In Archaeological Reminiscence of Millet's "Angelus," the low horizon line and the almost empty landscape emphasize the monumentality of the strange structure in the foreground. Dali transforms the Millet figures into monuments not because they are to be seen as dead symbols, but because they represent ever-present ancient principles, the foundations of human sexuality. Arnold Bocklin's evocative painting The Isle of the Dead informs the moonlit gloom of this powerful work, and cypress trees, symbols of death and finality, stress the atmosphere of fatalism. These supposedly universal principles, in a process of male initiation, are being shown at the bottom center to a small boy, a boy, perhaps Dali himself, who is also seen to the right, with a seated nurse; these two similar scenes underscore the contrast; between the innocence of childhood and the fears of adulthood.