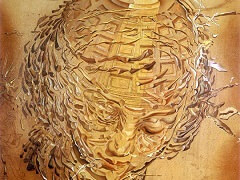

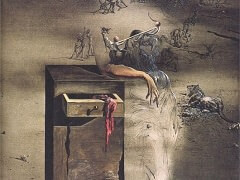

Bather, 1828 by Salvador Dali

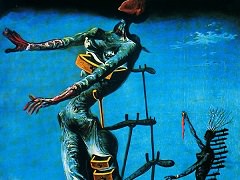

Building upon the extravagant figuration of acephalic women, flying breasts, and grossly distorted anatomies that entered his work in 1927, Dali executed a series of bather paintings in early 1928 in which he radically reconfigured the contours of the human body. Returning to a theme that had long captured his imagination, Dali now interpreted the venerable art-historical tradition of the erotic reclining nude in explicitly sexual terms.

Splayed out on a sandy beach for all to see, the body of Dali's Bather has been reduced to a hairy, tumescent big toe whose linear markings suggestively coalesce into a series of labialike folds around the nail. A red arabesque extends from the joint of the toe to the breast of a phantomlike creature in the upper left whose body has exploded into pieces that appear to float across the horizon. The erect female figure, a counterpart to the phallic toe, touches her thumb with her index finger, forming an open cavity in her swollen hand. Despite an obvious allusion to intercourse, however, the "male" and "female" protagonists of this sexual drama are only indirectly joined by the veinlike coil that extends from the toe. Graphically mapping an erotic exchange, the red arabesque, the phallic toe, and the enlarged hand tell a story of unfulfilled desire expressed through onanism.

In a text of the following year entitled ".. . The Liberation of the Fingers . ." Dali more explicitly pursued the associations of the phallus/finger/toe. Discussing his friendship with a largely uncultured character named Eugenio Sanchez, whom he met during his military service the preceding year, Dali describes how upon introducing his friend to certain surrealist texts in order to encourage his faculties of free association, he was astounded to hear him utter the phrase, "there is a flying phallus." Recognizing that his friend could not have had prior knowledge of Freud's discussion of the winged phallus in ancient art, as explored in his 1910 essay "Leonardo da Vinci and a Memory of His Childhood," Dali muses on the collective psychoanalytic meaning of hypnagogic images - in this case, the detached finger/flying phallus - derived just before falling asleep. To be sure, Dali's bather paintings of 1928 testify to the presence of unconscious desire as an agent of transformation for the subject both in dreams and in the physical world. In the highly suggestive, albeit deadpan, photographs of phallic "erect" fingers that illustrate ". . . The Liberation of the Fingers . . . ," that presence is rendered explicit.

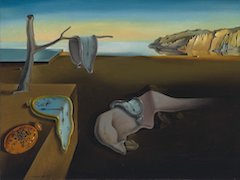

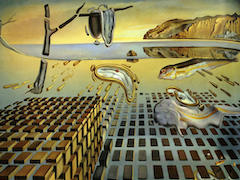

Numerous sources have been proposed for Dali's change in style at this time. On the one hand, the grossly distorted anatomy of the big toe (which looks ahead to Dali's anamorphic self-portraits in such paintings as The Persistence of Memory of 1931 owes a clear debt to Picasso's gargantuan bathers of the early to mid-1920s. Closer to the spirit of the painting, however, is the work of Andre Masson, Yves Tanguy, Jean Arp, and Joan Miro, in whom Dali expressed a keen interest at this time. Masson's sand paintings of 1926-27 establish an immediate precedent for Dali's unorthodox use of new media, as do Picasso's series of "guitars" of 1926, in which lowly, debased materials are attached to soiled, cardboard grounds. Dali's penchant for organic, biomorphic shapes, in contrast, points to the influence of Tanguy, Arp, and especially Miro, whom Dali had met at that time. In a short text on his Catalan colleague, published in June 1928, Dali waxed poetic about Miro's elemental figuration and economy of means:

Joan Miro knows how to clearly divide up an egg yolk, in order to make possible the appraising of the astronomical course of a head of hair. Joan Miro brings the line, the point, the slight stretching out of shape, the figuration meaning, the colors, back to their purest elemental magical possibilities."