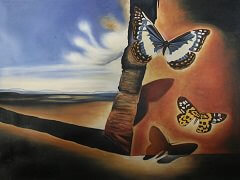

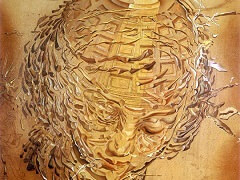

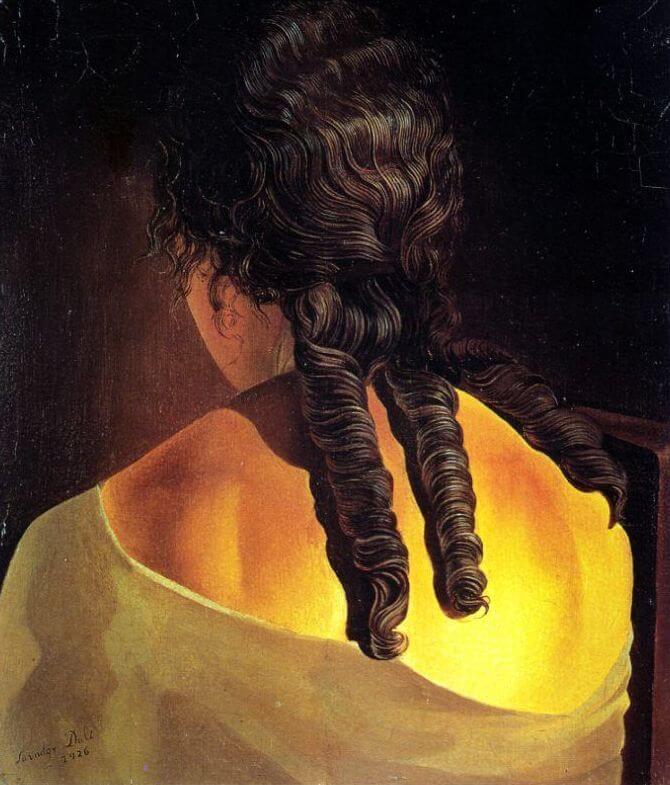

Girl's Back, 1926 by Salvador Dali

Concurrent with his work at the Real Academia de San Fernando and his interest in the neoclassicism of both Picasso and Ingres, a growing sense of realism had begun to enter Dali's painting in 1925. In an undated letter to Federico Garcia Lorca of the following year, Dali discussed his latest experiments in the context of his new passion for Dutch art: "I dream of going to Brussels to copy Dutch painting in the museum. You have no idea how much of myself I have put into my painting, how much affection I feel as I paint my windows open to the rocky sea, my baskets of bread, my girls sewing, my fish, my skies resembling sculptures." Two years later, in an important theoretical text entitled "The New Limits of Painting," Dali defined his interest in Dutch art with greater clarity, emphasizing the viewer's relation to the scene of representation as a subject in the world who actively scans the visual field, mapping and cataloging its manifold incidents. Singling out Rembrandt's Paintings and Vermeer's paintings as "case of the highest, most humble, and most dramatic probity" in the history of the "proper way of looking," Dali adapted the descriptive impulse in Dutch art to his own painting.

Even before Dali's first trip to Paris and Brussels in April 1926, during which time he had the opportunity to study Dutch and Flemish painting in some detail, he demonstrated a keen interest in the work of Vermeer and his contemporaries. In early 1926 Dali's uncle Anselm provided his nephew with a book on Vermeer, which supplemented the little monograph on the Dutch painter from the Gowans Art Books series that the artist had treasured since his youth. At the same time, Dali's technique acquired greater precision, and his decision to paint on panel in a quasi-miniaturist scale suggests that he consciously sought to imitate the effects of the Dutch and Flemish masters he so admired. Indeed, in Girls Back Dali lavishes particular attention on his sister's hair, which, gathered by a clasp just above the nape of her neck, extends in three tight coils that slither down her back, perhaps recalling the tuft of hair that escapes from the braided coiffure of Vermeer's Lacemaker. The heightened realism of Dali's depiction of the hair in turn contrasts with the more summary treatment of Ana Maria's dress and the exposed surfaces of her face and back, pointing to the range of stylistic idioms with which Dali worked at this time.