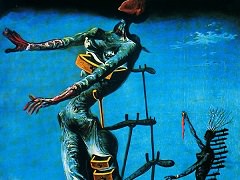

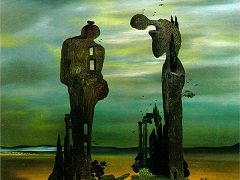

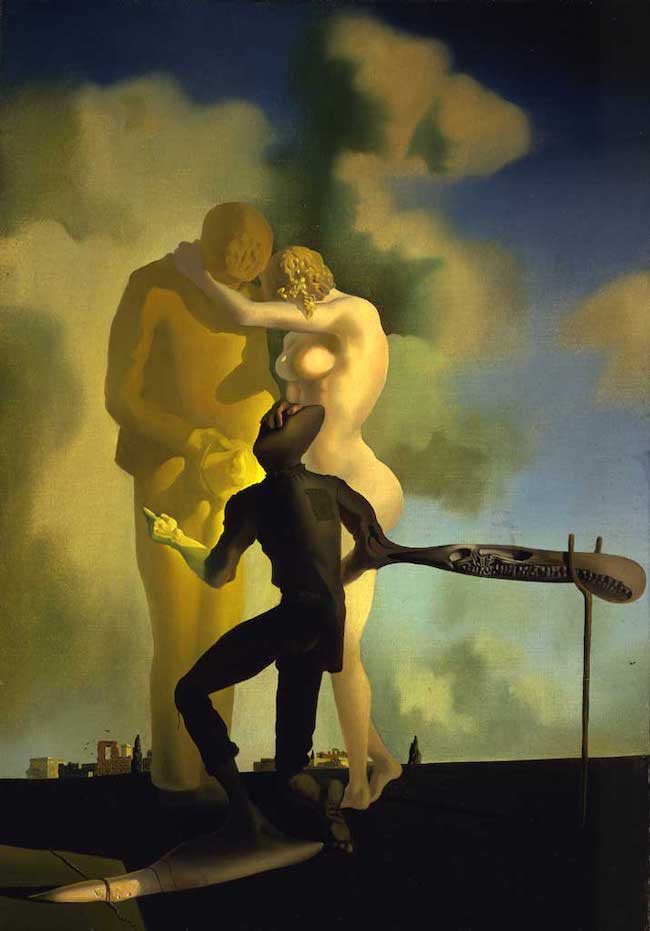

Meditation on the Harp, 1933 by Salvador Dali

In 1933 Dali embarked on a series of paintings based on the Angelus, Jean Francois Millet's popular masterpiece of 1858-59 (Louvre, Paris). The interest Dali took in the painting matched its mass appeal as an iconic image of peasant piety. Not only did a reproduction of the painting hang in the hallway of Dali's grade school in Figueres, but almost from its inception, the Angelus was widely reproduced in a variety of print media, ultimately appearing in the form of mass-produced objects, such as tea sets, inkwells, and pillow shams. This peculiar migration of a sentimental academic painting from the walls of the museum to popular kitsch fascinated Dali, who documented the process with the rigor of a social scientist.

Dali's approach to the Angelus theme mimics the psychoanalytic process itself. His "case study" owes more than a little to Sigmund Freud's 1910 essay Leonardo da Vinci and a Memory of His Childhood, with the significant exception that Dali is not in the least interested in the biographical facts of Millet's life. It is the psychoanalytic status of the Angelus as a cultural icon that Dali seeks to explore. The fact that the painting had been slashed and seriously damaged on August 12, 1932, by a deranged unemployed engineer named Georges Pierre-Theophile Guillard only confirmed Dali's suspicion that Millet's painting structured a cultural myth.

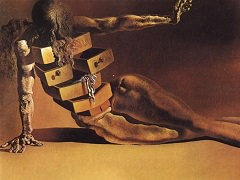

Dali explores his own "delirious" associations with the Angelas in Meditation on the Harp. The fork that is stuck in the earth in Millet's painting (in Dali's reading, an allusion to sexual intercourse) has been transposed into a crutch that supports an anamorphic, skull-like appendage that extends from the foreground figure's elbow. The conic head of this figure and his grotesque hornlike left foot relate to Dali's imagery of the grasshopper child, who, in the Oedipal triangle of the Angelus scenario, now represents the couple's dead son. The sexual aggression and incestuous desire of the mother for the son is suggested by her nudity, while the largely phantom figure of the male peasant bows his head in a gesture of shame rather than piety; his hat covers the site of his ignominy.