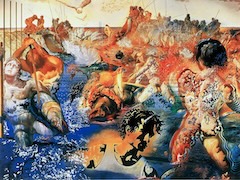

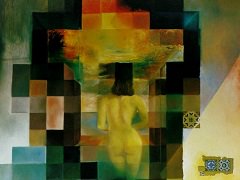

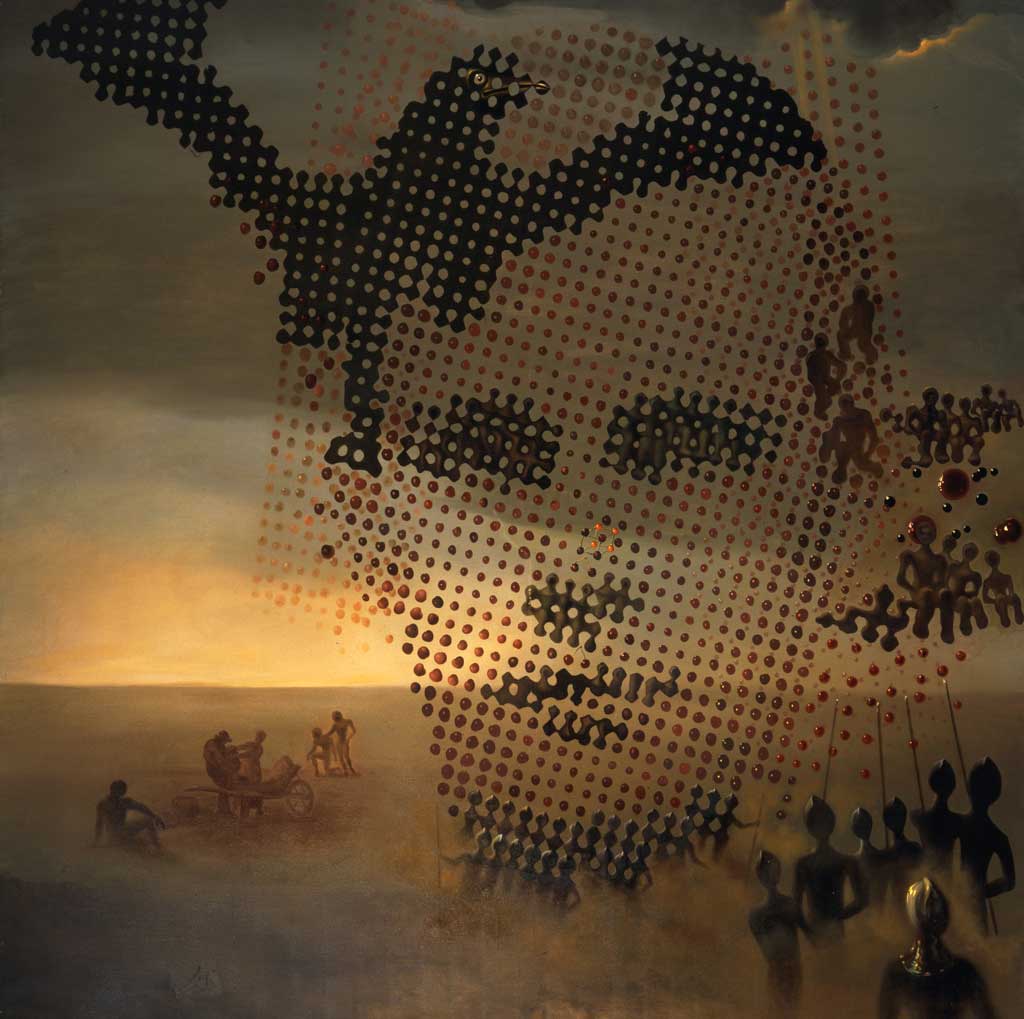

Portrait of My Dead Brother, 1963 by Salvador Dali

Dali returns to the theme of mythic autobiography in Portrait of My Dead Brother. In a text that postdates the painting, The Unspeakable Confessions of Salvador Dali, the artist recounted the traumatic events surrounding his older brother's death:

As is known, three years after the death of my seven-year-old elder brother, my father and mother at my birth gave me the same name, Salvador, which was also my father's. This subconscious aime was

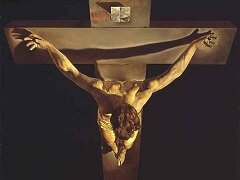

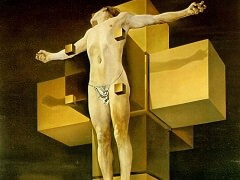

aggravated by the fact that in my parents' bedroom - an attractive, mysterious, redoubtable place, full of ambivalences and taboos - there was a majestic picture of Salvador, my dead brother, next to a

reproduction of Christ crucified as painted by Diego Velazquez; and this image of the cadaver of the Saviour whom Salvador had without question gone to in

his angelic ascension conditioned in me an archetype born of four Salvador's who cadaverized me. The more so as I turned into a mirror image of my dead brother.

I thought I was dead before I knew I was alive. The three Salvador's reflecting each other's images, one of them a crucified God twinned with the other who was dead and the third a dominating father,

forbade me from projecting my life into a reassuring mold and I might say even from constructing myself. At an age when sensibilities and imagination need an essential truth and a solid tutor, I was

living in the labyrinths of death which became "my second nature." I had lost the image of my being that had been stolen from me; I lived only by proxy and reprieve.

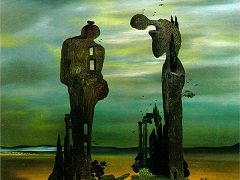

The apocryphal nature of Dali's self-sacrifice in Portrait of My Dead Brother is underscored by the fact that that image of the dead Salvador is an elaborate fiction. The visage of the child, who appears to be an adolescent boy, does not correspond to either Dali, but, rather, is meant to suggest a generic image of wholeness and completion (indeed, the enormous head looms large over a desolate landscape). What is more, the vulture that merges with the figure's head establishes a dual psychoanalytic and psychobiographical narrative for the scene: it represents the maternal vulture, about which Sigmund Freud wrote in his essay Leonardo da Vinci, A Memory of His Childhood - an image of incestuous desire - and it restates the theme of predatory female aggression, which Dali had explored in his Archeological Reminiscence of Millet's "Angelus", represented here in the scene of a peasant couple by a wheelbarrow. Indeed, Dali was explicit about his literary sources. In a statement published in the catalog accompanying his 1963 show at Knoedler Gallery, New York, he explained:

The Vulture, according to the Egyptians and Freud, represents my mother's portrait. The cherries represent the molecules, the dark cherries create the visage of my dead brother, the sun-lighted cherries create the image of Salvador living thus repeating the great myth of the Dioscuri Castor and Pollux.