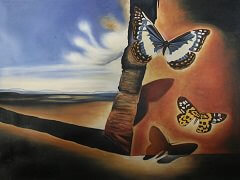

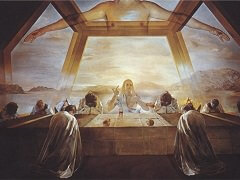

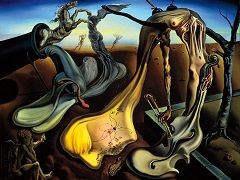

The Angel of Port Lligat, 1952 by Salvador Dali

Dali painted two versions of The Angel of Fort Lligat in 1952. The second version, in a private collection, is far more worked up in the manner of Landscape of Port Lligat. There are also notable differences in iconography: subsidiary figures are absent from the second version, while the angel's coiffure in this painting identifies the figure as Gala.

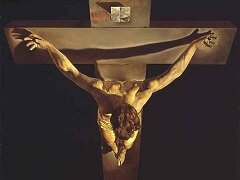

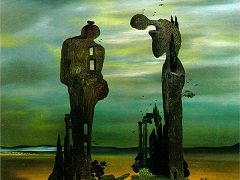

Almost from the moment he met her, Dali created an elaborate mythology around the figure of Gala, whom he imagined as both his artistic muse and the mysterious child-woman. Following his return to Port Lligat in 1948, Dali added Madonna and divine messenger to this cast of symbolic characters. In two well-known paintings of 1949 and 1950 entitled The Madonna of Port Lligat, a statuesque Gala in the pose of a Raphaelesque Madonna is enthroned on an elaborate altar, her hands clasped in prayer with the infant Jesus on her lap. Characteristic of Dali's transformation of his native landscape into a site of a divine communion, Gala appears to float above the sea and the terraced hills of Port Lligat. Dali employed a similar conceit in his great Christ of St. John of the Cross of 1951, in which a radically foreshortened Christ hovers over the bay of Port Lligat, the foot of his cross directly aligned with a small fishing boat on the shore (the same vessel appears in The Angel of Port Lligat). Evoking Port Lligat as the site of a mystical communion among himself, God, and nature, Dali wrote in The Secret Life:

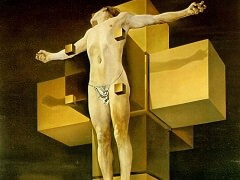

Port Lligat: a life of asceticism, of isolation. It was there that I learned to impoverish myself to limit and file down my thinking in order that it might become effective as an ax, where blood had the taste of blood, and honey the taste of honey. A life that was hard, without metaphor or wine, a life with the light of eternity. The lucubrations of Paris, the lights of the city, and of the jewels of the Rue de la Paix, could not resist this other light-total, centuries-old, poor, serene and fearless as the concise brew of Minerva. At the end of two months at Port Lligat I saw rising day after day before my mind the perennial solidity of the architectural constructions of Catholicism. And as we remained alone - Gala and I, the landscape and our souls - the ancient brows of the Minervas came more and more to resemble those of Sistine Madonnas of Raphael, bathed in a light of oval silk.