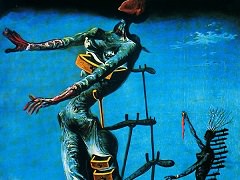

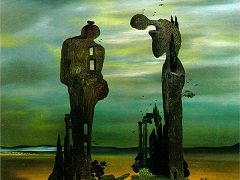

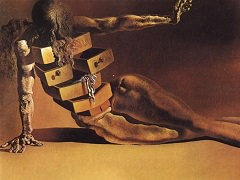

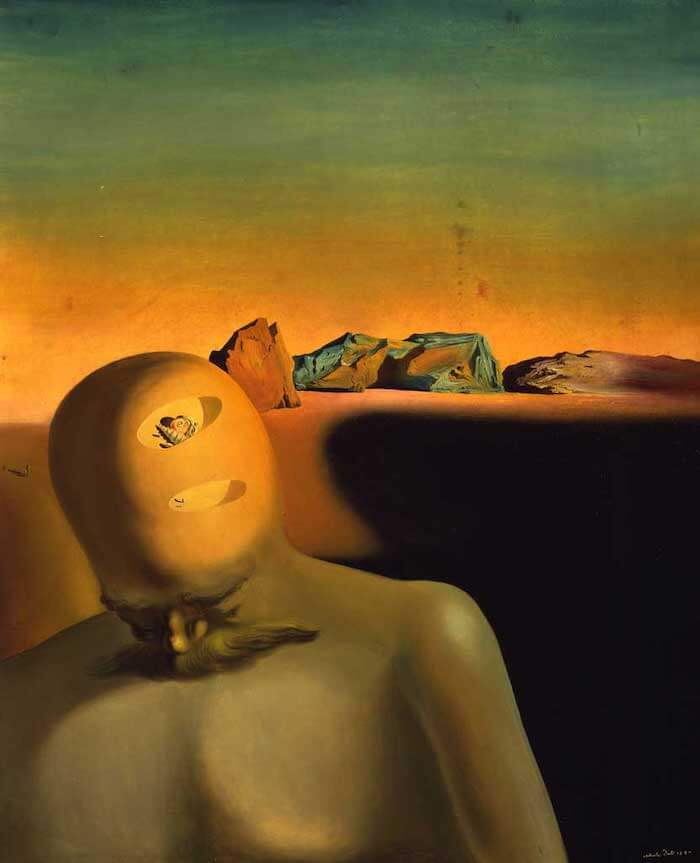

The Average Bureaucrat, 1930 by Salvador Dali

Upon receiving word on December 6, 1929, of his expulsion from the family home, Dali shaved his head in an act of defiance against the threat of symbolic castration. Over the next four years he produced a series of paintings in which the image of the father obsessively dominated his subject matter in the form of mythical and historical figures (William Tell, Lenin, civil servants, the grasshopper child, members of the family group from Jean-Francois Millet's Angelas, and, later, Sigmund Freud) with grotesquely enlarged, often distorted, bald heads or hydrocephalic, anamorphic skulls. Referring at once to the threat of emasculation by a ruthless father and the sublimation of unresolved Oedipal desires, these disturbing paintings collectively explore the theme of masochism: the desire for and resistance to symbolic incorporation and authoritarian control.

The image of the bureaucrat - a clear reference to Dali's father, who was a notary - first appears in The Average Bureaucrat of 1930. The enormous, somewhat ridiculous figure looms large over the twilight landscape of the Emporda, dwarfing the couple (Dali and his father, or, more generally, an Oedipal group) in the middle ground. The convoluted nature of the bureaucrat's thought is suggested by the presence of snail shells in craterlike openings in his head.' The shells, in Freudian symbolism, allude to female genitalia, while the openings transform this representative of bourgeois law and order into an elaborate, soft Swiss cheese of sorts.