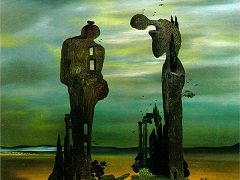

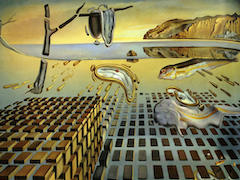

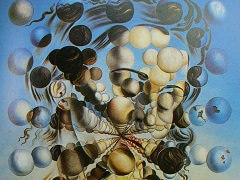

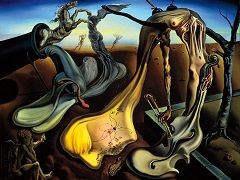

The Dream, 1931 by Salvador Dali

The Dream gives visual form to the strange, often disturbing world of dreams and hallucinations. Ants cluster over the face of the central figure, obscuring the mouth, while the sealed, bulging eyelids suggest the sensory confusion and frustration of a dream. The man at the far left - with a bleeding face and amputated left foot - refers to the classical myth of Oedipus, who unwittingly killed his father and married his mother. The column that grows from the man's back and sprouts into a bust of a bearded man refers to the Freudian father, the punishing superego who suppresses the son's sexual fantasies. In the distance, two men embrace, one holding a golden key or scepter symbolizing access to the unconscious. Behind them, a naked man reaches into a permeable red form, as if trying to enter it.

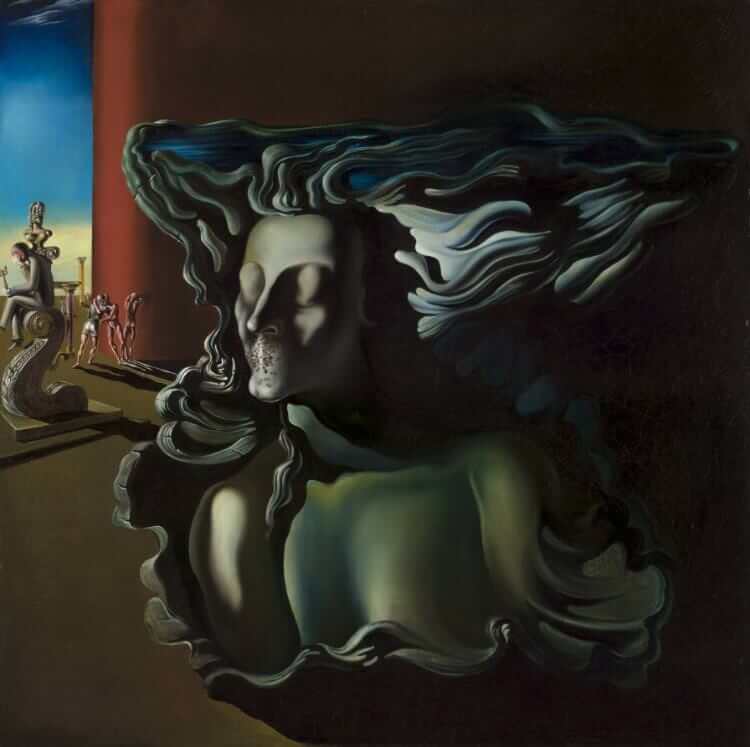

A well-read student of Freud, Salvador Dali - who never used drugs and only drank alcohol (especially champagne) in moderation - turned to a most unusual way to access his subconscious. He knew that the hypnogogic state between wakefulness and sleep was possibly the most creative for a brain. Like his fellow surrealists, Dali considered dreams and imagination as central rather than marginal to human thought. Dali searched for a way to stay in that creative state as long as possible just as any one of us on a lazy Saturday morning might enjoy staying in bed in a semi-awake state while we use our imagination to its fullest. He devised the most interesting technique.