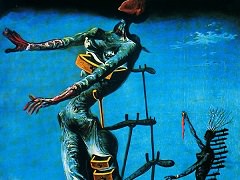

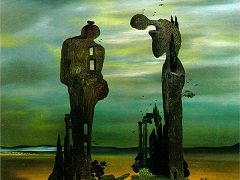

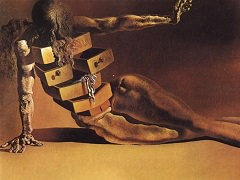

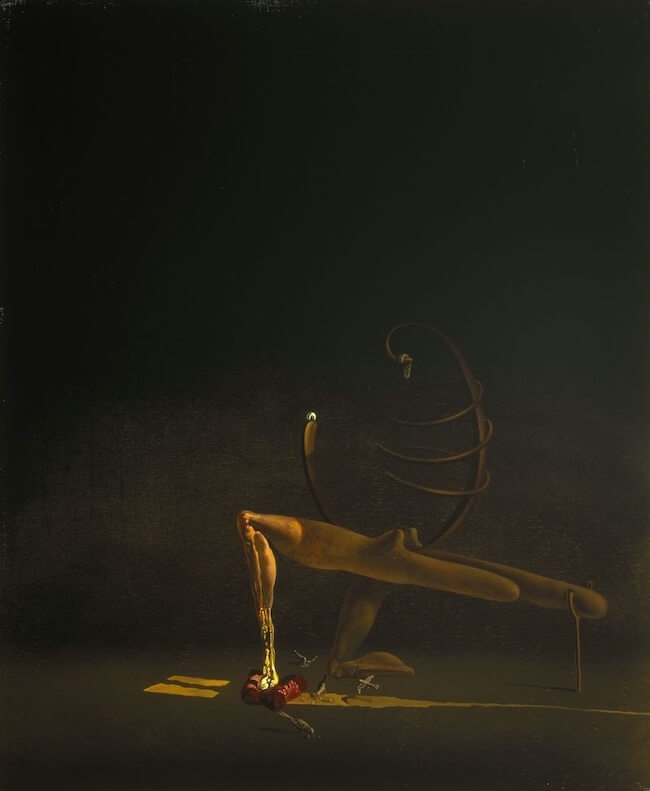

The Javanese Mannequin, 1934 by Salvador Dali

Like numerous works of 1933 and 1934, including the Angelus series, the imagery of The Javanese Mannequin relates to the forty engravings Dali produced for Albert Skira's deluxe edition of Les Chants de Maldoror, Isidore Ducasse's (1846-70) haunting novel of 1869. The ossified figure of the mannequin, half bone, half rotting flesh, appears as an illustration to Maldoror's second song, where it relates to the general theme of putrescence and decomposition. In the painting, a worm or maggot hangs from the very top of the mannequin's curved spinal column, while on the ground below, birds pick at crumbs that seem to have their source in the rotting, ulcerated flesh of the figure's right leg or the loaflike protrusion of its buttocks. As he reconfigures the human body, Dali, like his colleague Georges Bataille, establishes an anatomy of the abject.

Bataille's project, as outlined in his dictionary entries for Documents in 1929-30 and in subsequent short essays, involved inverting the hierarchies of the ideal human form. The impact of his thought in the early 1930s extended to artists as diverse as Joan Miro and Alberto Giacometti. In 1933 Picasso himself produced eighteen drawings of hybrid humanoid figures that he imagined as pieces of furniture and still-life objects. Published in the first issue of Minotaure magazine (February 1933), Picasso's series, entitled "An Anatomy," must have captured Dali's imagination, for he produced an engraving that same year in which he added his own figuration of rotting corpses and dismembered bodies to the ground of a print by Picasso with related imagery, attempting to pass off his hybrid Figures surrealistes as a collaborative effort.