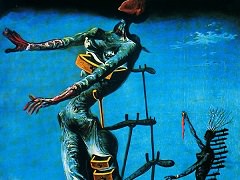

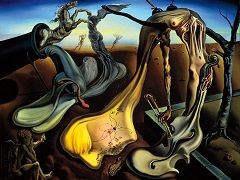

Beigneuse, 1828 by Salvador Dali

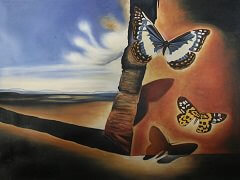

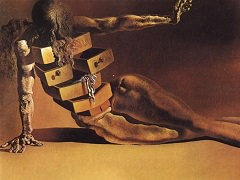

Beigneuse is a thematic pendant to Bather of 1928. Although slightly larger, it reprises the subject matter of the other painting and of the bather series in general: an enormous hand with an extended phallic pinky finger has replaced the tumescent big toe of Bathe; while the feet in Beigneuse, however exaggerated, are significantly reduced in size and scale. In contrast to the other painting, however, the predatory sexuality of the bather is fully manifest. The diminutive face is reduced to two stylized black circles for eyes, while the serrated open mouth suggests a vagina dentata, an obvious allusion to the threat of castration. With a hideously deformed, sagging left breast and sickening flesh the color of PeptoBismol, Beigneuse is an image of decay, putrefaction, and death.

Dali conceived the painting as a frontal attack on the Catalan art establishment and its adherence to age-old canons of ideal feminine beauty. The sandy beach on which the figure reclines at once establishes a concrete, material setting for the nude, in that it consists of actual sand embedded in the paint, and acts as an exhortation to touch, its coarse texture existing in marked contrast to the smooth surface of the figure's flesh. The friction that is established between these dissonant textures appears to have both a sexual and an art-historical meaning, calling to mind Max Ernst frottage technique, in which pigment is rubbed onto canvas or paper that has been laid on a rough surface, revealing the underlying texture. In French slang, however, the verb frottager - "to rub" - also refers to the grinding of bodies in an erotic encounter, a meaning that cannot have escaped Ernst or Dali.

The theme of the overtly sexual bather in Dalf's work in turn bears striking affinities with a contemporaneous series of equally lewd "Spanish Dancers" produced by Miro in the late winter/early spring of 1928. Although it is unlikely that Dali knew of this series (Miro executed the "Spanish Dancers" in Paris), he was familiar with his colleague's much publicized desire to "assassinate" painting. (The "Spanish Dancers" incorporates unorthodox materials, such as sandpaper, feathers, cork, hat pins, and illustrations from retail catalogues, in a calculated assault on the tradition of belle peinture.) In the final section of his essay "The New Limits of Painting," which Dali published in three installments in February, April, and May 1928, as he worked on the "Bather" series, he championed surrealism's attack on the cultural norms of bourgeois society, especially the investment in high art as a moral and spiritual absolute:

The assassination of art, what a beautiful tribute!! The Surrealists are people who honestly devote themselves to this. My thought is quite far from identifying with theirs, but can you still doubt that only those who risk all for everything in this endeavor will know all the joy of the imminent intelligence. Surrealism risks its neck, while others continue to flirt, and, while many put something aside for a rainy day."